Managing Tomorrow Today

By Kelsey Allen

Professors in the Management Department in the Trulaske College of Business are publishing research that’s challenging assumptions that drive decision-making in the workplace. Here’s a look at four researchers and their findings.

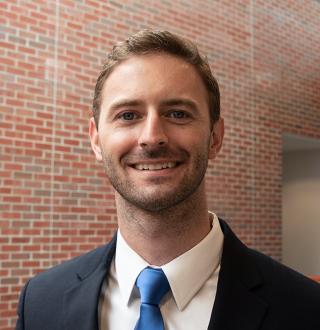

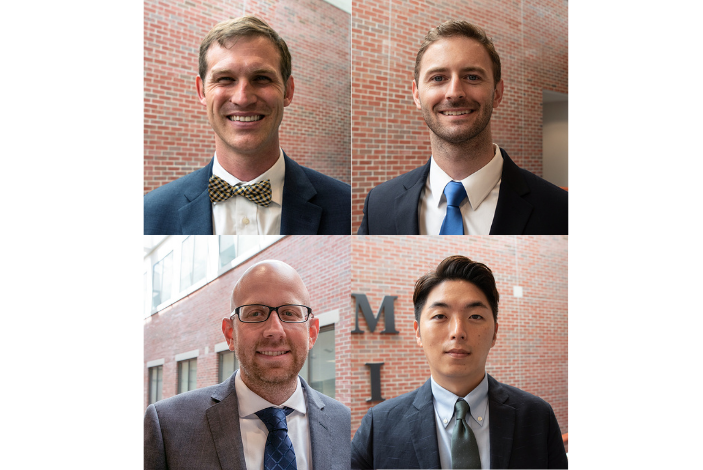

Rethinking the Employment Application

Screening job applicants based on their prehire work experience is one of the most widely used methods by which organizations assess job applicants. New research from management Assistant Professor John Arnold shows that this approach is often a mistake.

While past research studies of job experience found a moderate relationship between current experience and job performance, Arnold’s research specifically measures prehire work experience, or experience workers have acquired before they enter a new organization, such as years of work experience, number of previous jobs held and whether they possess experience in the type of job to which they are applying.

“Prehire work experience was only very weakly related to job performance, and it was unrelated to turnover at all,” says Arnold, an expert on human resources staffing. Yet Arnold’s analysis of online job ads showed that 82% of jobs either required or preferred experience. “What that means is that organizations that use these types of screening measures as part of their employee selection process are screening out good candidates along with the bad candidates at almost equal rates.”

For example, a company wants to know how many years of prehire work experience a candidate has. It might prefer applicants with at least five years of work experience. “One of the problems with that is that people who have been great in their jobs for five years have five years of work experience — but so do people who have been rather lousy or have sort of nominal performance in their jobs for five years,” Arnold says. “They all have five years of work experience. So, it just doesn’t tell us anything about how they actually performed in the past.”

These findings have important implications for HR professionals and hiring managers, especially in the midst of a labor shortage. “Organizations really should be more conscientious about how they're screening out applicants who could be great applicants,” Arnold says. Other selection procedures that are more correlated with job performance include cognitive ability tests, structured interviews and situational judgment tests.

Published in Personnel Psychology, the paper, “A meta-analysis of the criterion-related validity of prehire work experience,” received the Personnel Psychology 2021 Best Paper Award.

Monitoring Remote Workers

More employees are working from home — and more employers are adopting monitoring software to keep an eye on their work-from-home employees. Applications can take screenshots of workers’ computers at regular intervals, do keystroke logging and record screens. These tools can track employee productivity and help companies enforce data security policies.

Many company leaders intuitively assume that monitoring reduces deviance, such as loafing, theft, gossip or verbal abuse. But monitoring may not always serve its intended function. New research from management Assistant Professor John Bush shows that monitored employees may actually engage in higher levels of deviance.

“What’s happening is employees are engaging in deviance in areas where the organization is not actually monitoring,” Bush says. “So, if you’re monitoring in one way, employees may do other things that are deviant in response to that monitoring practice.”

For example, an organization might monitor the use of employee emails for personal reasons. While using work email for personal purposes is reduced, employees end up sending personal emails from their own personal accounts while at work.

Bush found that monitoring paradoxically creates conditions for more deviance by diminishing employees’ sense of agency.

“Monitoring increases the extent to which individuals feel that they do not have control over their own decisions,” Bush says. “Once they have this feeling, employees become more likely to displace responsibility or essentially feel like they should not be blamed for their behavior because they either do not control it or they are just doing what they’re told.”

One way employers can mitigate the relationship between monitoring and sense of agency is by treating their employees fairly overall. Then employees are more likely to believe that monitoring will not be used to undermine their sense of agency and cause them harm.

“When employees perceived an overall sense of justice and fairness at their organization, then we did not see as strong of a negative impact of monitoring,” Bush says. “If you do feel like you need to monitor employees, it’s important for employees to feel that all of those decision-making procedures are fair.”

Published in the Journal of Management, the paper, “Stripped of Agency: The Paradoxical Effect of Employee Monitoring on Deviance,” received the Outstanding Practical Implications for Management Paper Award from the OB Division of the Academy of Management.

One reviewer noted: “This paper provides an important warning to managers that performance monitoring to regulate employee behavior can actually compel employees to engage in more (rather than less) deviance.” A second reviewer added that the research “is necessary, both from an ethical and a practical perspective, and has the largest potential to make a significant impact in the real world.”

Staying a Step Ahead of the Competition

Companies have historically looked predominately at other companies within their industry to spot rivals. Automakers looked at automobile companies, for example. But in an era of digital transformation, it’s becoming more common for indirect competitors to become direct rivals.

Take Amazon, which started as an online bookstore, primarily competing with local booksellers and Barnes & Noble. When it launched a cloud computing platform, it began competing with Microsoft, Google, Salesforce and IBM. And when it started its delivery services, USPS, FedEx and UPS became competitors. Similarly, smartphones disrupted the market for GPSs and digital cameras, and tech companies shook up the auto industry.

“In contrast to what was done before, which is looking at firm-level attributes, we need decision-makers and firm leaders to zoom out to see the bigger picture that their companies are embedded within,” says management Assistant Professor Stephen Downing, an expert in competitive dynamics. “What if you actually have threats coming from firms you haven't identified yet?”

To offer new guidance on how to think about competition, Downing studied thousands of competitive encounters over 10 years and developed a “hostility profile” that can guide business leaders in how to better spot, appraise and prioritize indirect competitors that stand to become direct rivals. The hostility profile provides four early signs:

- Diversification: Companies that are highly diversified in terms of the scope of their operations, products or services — such as Johnson & Johnson, 3M, and Berkshire Hathaway — are more likely to face competitive encounters.

- Asymmetric pressure: When one company faces competitive threats or pressures from many rivals and another company faces fewer, the tendency for the less-pressured firm to exploit the vulnerability of the more-pressured firm will make these types of firms more likely to engage each other.

- Degree of separation: Companies that are four or more degrees of separation away from a focal firm are unlikely to become direct rivals.

- Convergence: When technologies, capabilities, firms, industries or landscapes coalesce and networks converge, companies become closer and are more likely to experience competitive encounters among themselves.

“We need to rethink the industry boundaries as the starting point,” Downing says. “We need to actually look at how industries are converging or diverging with or from each other and how these new ecosystems are reshaping industries.”

The paper, “What you don’t see can hurt you: Awareness cues to profile indirect competitors,” was published in Academy of Management Journal.

Understanding Status Hierarchies

Humans are obsessed with status. While some theorists have argued that a single status hierarchy exists, management Assistant Professor Jung-Hoon Han argues not only that multiple status hierarchies exist but that they can be conceptualized based on their underlying value systems.

Contrasting underlying values are present throughout the business world: editorial commitment versus commercial viability in publishing, professionalism versus profit in law and science versus commercialization in high-tech industries. A huge movie fan, Han tested his theory in the context of the Hollywood film industry, which pits artistic values against commercial values.

“If all is equal, we would all want our status to be high in all dimensions, but it’s not that simple,” Han says. “Artistic and commercial values are both really strong, viable values, but in this context, artistic values are accorded much more respect.”

This status inconsistency has a profound — and surprising — impact on behavior. Han’s research shows that actors with higher artistic status were more likely to try and resolve their status inconsistency by improving their commercial status. “That’s why you see so many Oscar winners appearing in the Marvel franchise,” he says.

But actors whose primary status is commercial were less likely to try to enhance their artistic status. “When you’re trying to pursue something that seems out of your place, you might invite some backlash, so you feel an impediment in pursuing artistic status. Think of blockbuster movie stars trying to appear in art-house films. There won’t be that much of a positive reaction from the audience.”

The findings suggest the effect of hierarchy-level prestige is substantial and provides insights into why people may behave differently in the face of the same absolute level of status inconsistency.

“You really need to understand what kinds of values are out there and whether the values themselves have this hierarchical relationship,” Han says.

Managers would do well to consider their standing in a variety of different status hierarchies that value different characteristics and be aware of how status inconsistencies can influence whether it is more productive to invest in enhancing their secondary status or to focus on enhancing or maintaining their primary status.

The paper, “The two towers (or somewhere in between): The behavioral consequences of positional inconsistency across status hierarchies,” was published in the Academy of Management Journal.