To Infinity and Beyond

By Kelsey Allen

Student-entrepreneur Ed Ge leads a venture-backed startup that provides high-resolution aerial imagery and real-time data for mapping, surveillance and national security.

Ed Ge always wanted to push the boundaries of what is possible. As a kid growing up in the suburbs of Detroit, he took his cues from great emperors and generals, like Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar.

“I read so many history books my mom and dad had to hide them from the family library because they distracted me from my other studies,” he says. “There’s a book on naval warfare in the 19th century that I read front to back over and over and over to the point that the covers were falling off.”

Although he no longer dreams of being an astronaut or a Navy SEAL — or the king of Macedon, who, famed for his drinking, died when he was just 33 years old — he’s still daring to forge his own path. In August 2020, the senior Trulaske College of Business student went part time so he could work full time on his startup, Stratodyne, which was accepted into a major accelerator program in Silicon Valley and recently received a St. Louis Arch Grant.

He’s still planning on returning to MU after he graduates from the Alchemist Accelerator in spring 2021, but right now he’s focused on building the next generation of aerial monitoring vehicles.

“I never thought of myself as an entrepreneur,” Ge says. “But I’ve always known that, no matter what I did, I wanted to be the best.”

Exploring New Territory

For some, boredom may lead to addictive, impulsive or unproductive behavior. Not Ge. When he was bored in high school, he and some friends in the Aerospace Club attempted to live-stream pictures from cameras mounted on weather balloons that they launched into the stratosphere.

“Looking back on it, what we did was highly illegal,” says Ge, whose parents are both engineers. “But we didn’t know it at the time.”

At Mizzou, when boredom’s sisters — curiosity, imagination and wonderment — came calling, Ge and his high school friend Amit Pinnamaneni, now a computer engineering major at the University of Michigan, revived their space exploration project. This time, they had more resources, including two years of college courses under their belts and access to the 3D printing lab in the MU College of Engineering.

Their initial goal was to build a more affordable way to launch rockets. By sending a 3D-printed rocket up into the stratosphere on a high-altitude balloon, they thought they could more cheaply shoot the rocket into space.

“The idea was that at much higher altitudes we could save a lot of fuel and use smaller rockets to achieve orbit,” Ge says. “But that was still extremely cost-prohibitive.”

So they did what many entrepreneurs do.

The Entrepreneurial Pivot

When a farmer wants to assess biomass of their crops to create detailed production forecasting or a city’s water division needs to track erosion and vegetation growth around infrastructure in a remote setting, they might consider using aerial data — until they see how expensive it is. And when a government agency requires high-resolution aerial monitoring to detect risks, it has to wait at least a day, sometimes a week, for refreshed images.

“We realized that having the high-altitude platform up there in the stratosphere — the data that it can capture and gather is much more valuable than anything it can shoot into space from that altitude,” Ge says.

By relying on balloons, as opposed to aircrafts or satellites, Ge and his team can remain over targeted regions for long periods of time, providing a continuous stream of real-time data at pricing up to 15 times less than competitors.

“Our main value is the fact that we can get these images way faster than anyone else,” Ge says. “Not much changes on a farmer’s field between Week 1 and Week 2. But if you’re a government agency and you want to monitor a military base, for example, a lot can change between Hour 1 and Hour 2. That’s where we come in.”

Ready to Launch

They wanted to call the company Stratosphere Dynamics but opted for the shortened version: Stratodyne.

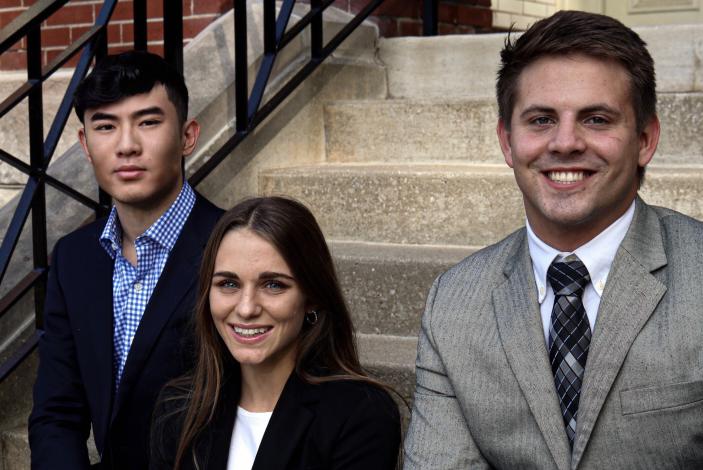

Putting Ge’s business school courses to the test, the team, which now also includes Tigers Bryce Edmondson, a finance and economics major, and Victoria Lofland, a physics major, formed a Delaware C Corp and started pitching venture capital companies to invest in Stratodyne.

“We got slaughtered,” says Ge, the CEO. “What I heard commonly was our team doesn’t have a lot of credibility because, well, we’re four college students.”

That’s when Stratodyne applied to the Alchemist Accelerator, a six-month program that focuses on scaling enterprise startups. Along with cloud credits, accounting and legal services, and other perks, the Stratodyne team gains access to feedback from other founders in the program and networking and coaching opportunities with veteran investors and venture capitalists.

“They know a lot of stuff that we don’t know, and there’s stuff that we don't know that we don’t even know we don’t know,” Ge says. “Being able to pick their brains is absolutely important for the company to survive. As is being able to leverage these connections, especially as a team of college students from the Midwest. If you don’t have a lot of pre-existing connections to venture capitalists and investors, a lot of them will not meet with you.”

At the end of the program, the team will pitch Stratodyne to a group of veteran investors and venture capitalists, hoping to add to the money raised in a pre-seed round led by TSVC, a major venture capital firm based in Silicon Valley, and the $50,000 Arch Grant. After graduating with their college degrees, Ge says the team plans to relocate Stratodyne’s headquarters from Columbia to St. Louis.

“The best thing about starting your own company, or being the CEO of one, is you have an impact on the greater corporate vision,” Ge says. “You are not only a part of something far greater than yourself; you also influence where that greater part goes.”